Joseph Burns (Part 2), October 13, 2019

Dublin Core

Title

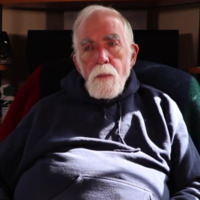

Joseph Burns (Part 2), October 13, 2019

Description

Joseph Burns shares stories of Le-Hi-Ho, LGBT activism, and personal relationships.

Publisher

Special Collections and Archives, Trexler Library, Muhlenberg College

Date

2019-10-13

Contributor

This oral history recording was sponsored in part by the Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium, with generous support provided by a grant to Lafayette College from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Rights

Copyright for this oral history recording is held by the interview subject.

This oral history is made available with a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0). The public can access and share the interview for educational, research, and other noncommercial purposes as long as they identify the original source.

This oral history is made available with a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0). The public can access and share the interview for educational, research, and other noncommercial purposes as long as they identify the original source.

Relation

Stories from LGBT Older Adults in the Lehigh Valley

Format

video

Language

English

Type

Movingimage

Identifier

LGBT-08

Oral History Item Type Metadata

Interviewer

Mary Foltz

Interviewee

Joseph Burns

Original Format

video

Duration

1:53:05

OHMS Object Text