Bruce Sheftel, May 31st, 2017

Dublin Core

Title

Bruce Sheftel, May 31st, 2017

Description

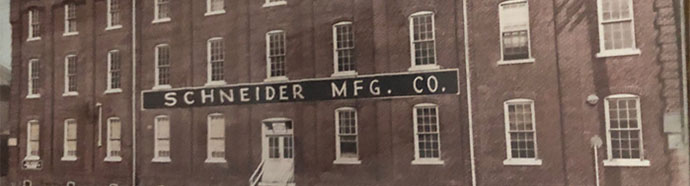

Bruce Sheftel talks about how his grandfather (Abe), a young immigrant, started as a junkman with his brother-in-law. Later, when Abe’s sons (Milt and Harold) were in the business, they bought textile waste from the many mills that existed up and down the Lehigh river. Harold focused inside the factory/warehouse and Milt (Bruce’s father) focused outside the factory selling the processed textile waste to customers. Their main customer was Crane & Company who used cotton rags to make US currency. The final generation in this business (sons of Milt and Harold) witnessed the disappearance of the U.S. textile waste industry as the textile and needle trade industry moved overseas.

Publisher

Special Collections & Archives, Trexler Library, Muhlenberg College

Date

2017-05-31

Rights

Copyright for this interview is held by Muhlenberg College. This oral history is made available with a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0). The public can access and share the interview for educational, research, and other noncommercial purposes as long as they identify the original source.

Format

video

Identifier

LVTNT-15

Oral History Item Type Metadata

Interviewer

Susan Clemens-Bruder

Gail Eisenberg

Interviewee

Bruce Sheftel

Duration

01:52:27

OHMS Object Text